It’s that time of year again… There’s no escaping Zwarte Piet. Last year I wrote an essay on the “Black Pete” phenomenon and the Dutch postcolonial condition in Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam’s publication Project 1975. I have posted the text, “Piet Zwart & Zwarte Piet” (minus the illustrations) in the articles section of this site. Happy holidays, but watch out for that colonial hangover!

Month: November 2014

Margins and Occupations

The new issue of the journal ARTMargins features a roundtable on “the critical archive,” in which I’m one of the participants. I’m erroneously identified as a lecturer in art history at the University of Amsterdam (or UvA). I teach at the other Amsterdam-based university, the Vrije Universiteit, a.k.a. VU University Amsterdam. My recent blogpost about the crisis at the UvA has apparently also created some confusion on this point. My post was made in solidarity with my UvA colleagues (and their students). The two universities collaborate on a number of levels, including joint MA programmes, and we are ultimately all in the same boat. Earlier this year, when the VU’s Faculty of Earth and Life Sciences faced similarly draconian cutbacks, students actually appropriated a flyer for the famous 1969 occupation of the UvA’s headquarters – the Maagdenhuis.

When the UvA’s humanities students announced their protests, the university’s newspaper Folia noted that their calls for resistance were “reminiscent of the 1960s.” If the VU students’ flyer ironically acknowledges that the potential for student protest and resistance has lain dormant for all too long, Folia‘s remark reads as a subtle putdown. Oh, those hipster students and their retro fads! It is of course true that the tables have been turned: if once the university was there to be taken, to be occupied, by progressive forces, today’s occupation actually starts in the boardroom and proceeds with through a dialectic of shock therapy (as in the current UvA situation) and the steady hollowing-out of rights and of forms of life through “baby steps” gradualism.

In 1968, the Situationist-dominated “Council for Maintaining the Occupations” at the Sorbonne put out a poster decreeing the “End of the University.” Now that universities have been occupied by rather different forces, a dystopian version of this utopian promise is a daily lived reality.

Holland in 2014: A Cultured Nation

My colleagues at the humanities department of the University of Amsterdam (UvA) are facing a bloodshed: massive layoffs and the drastic reduction or closing down of entire programmes. Students and staff are united in protesting against the cutbacks, for the logic is as ever presented as an economic necessity without alternatives. For keeping up with the developments, there’s this facebook page is here: https://www.facebook.com/Humanitiesrally

Looking for media coverage, I couldn’t help but notice a striking and symptomatic pair of articles on the site of Het Parool, both published on 12 November: whereas one deals with the UvA protests, the other reports on a speech by Amsterdam’s alderwoman for culture, Kajsa Ollongren. Ollongren touts Amsterdam’s “cultural” potential, which is to says its potential for further economic growth through cultural tourism: “We have to create room for talents and the creative industry. I want the major museums to set the trend and become a magnet for talent. I’m hoping for a lot of new initiatives.” (My translation; the original doesn’t sound much better.) This is the “creative industries” ideology in a nutshell: produce meaningless rhetoric about “talent” while trying to bilk the rubes (pardon me, to attract tourists) with a limited and conservative palette of spectacularized “top culture,” and while striping down or even destroying institutions that actually preserve and generate cultural knowledge.

In the case of universities and other institutions, this destruction takes the form of a relentless financialization, with a highly paid managerial caste taking over and imposing the logic of financial derivatives on what used to be a public institution. An in-depth analysis of how this happened in the case of the UvA can be found here or here. While this takeover by finance capital is obviously far from limited to this country, Dutch academics so far seemed to be willing to put up with almost anything. It’s high time for those days (years, decades) to end.

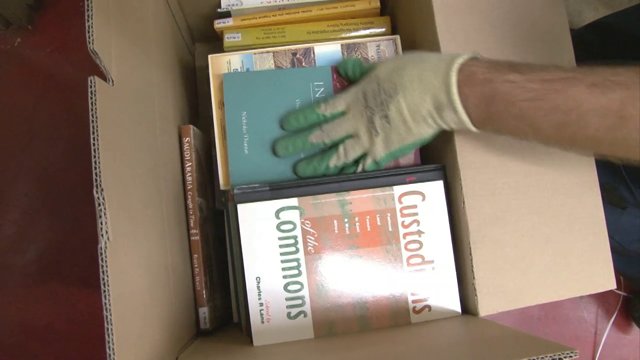

Image: A still from Bregtje van der Haak’s terrific documentary Digital Amnesia showing the packing of books from the Royal Tropical Institute; this unique library was closed down and the collection was eventually shipped to Egypt, where the new Library of Alexandria was happy to receive it.

Louise Lawler’s A Movie Will Be Shown Without the Picture

From November 27 to December 3, If I Can’t Dance will be hosting the Performance Days festival in Amsterdam. This occasion will also see the launch of four new books that have resulted from “Performance in Residence” research projects by Gregg Bordowitz, Jacob Korczynski, Grant Watson and myself. My publication, Louise Lawler’s “A Movie Will Be Shown Without the Picture,” was edited together with Tanja Boudoin and contains an introduction by Frédérique Bergholtz and Tanja, short texts by Eve Dullaart, Debbie Broekers and Daniël van de Poel, as well as my own extensive article—not to mention plentiful visual documentation of Lawler’s A Movie project plus related pieces, thanks to archival excavations by Louise and by Kenneth Pietrobono.

I’ve said this before, but I’ll say it again at a moment when the crisis of the Dutch universities’ humanities departments is rapidly deepening, and any form of meaningful activity may soon be made impossible by our Stalineoliberal overlords: it is heartening to see that small art organizations, however precarious their own position may be, invest in research and in critical practice.

You must be logged in to post a comment.